The summary of a talk by

Alistair B. Fraser

Professor of Meteorology,

The Pennsylvania State University

|

The Web: a Classroom Sans Walls

| The web of our life is of a mingled yarn |

The summary of a talk by

|

| The web of our life is of a mingled yarn |

Abstract

The delivery of course material has changed forever as two roads converge: access and animation. Interactive resources can now be delivered into classrooms and dormitories across the world.

Background

In the middle ages and colonial North America, the classroom technology of choice was the scholar's board (which evolved into the horn book), a paddle-shaped piece of wood upon which a student inscribed a lesson being dictated. Like the modern computer, the scholar's board was interactive and would display text and images. Like the World Wide Web, its material could be transported from place to place. But it was slow --- infinitely slow by modern standards. Having a much better match with the human perception and processing system, the computer opens up many pedagogical advantages over not only the scholar's board, but over its descendant, the blackboard, especially when the computer is used in conjunction with the web.

If the computer offers advantages over the pedagogical technology of previous generations, what are they? That there might be any at all is not entirely obvious to most participants in classes or seminars for which the presenter has --- as he might unfortunately put it --- computerized his lecture. Generally the presentation takes the form of bulleted text supplemented by a few gratuitous (and irrelevant) images and pointlessly cute transitions. The problem is that the material being presented has been cribbed from the yellow pads of paper previously used to assemble notes for the blackboard. Accordingly, the imagination that went into its preparation has been implicitly constrained by the presentation capabilities of the blackboard. Nowhere apparent is there any pedagogical value added as a result of the availability of the more powerful platform. Nowhere apparent is the realization that the constraints upon communication have receded.

For a couple of years now, the Web has been pressed into service to do exactly the same thing (but without the cute transitions). Indeed, there are many examples of course material available on the Web, but virtually all of them represent electronic transcriptions of that which was once offered in print. This use of the Web has certainly provided the material with broad accessibility, but it is not clear that the imaginations of most of those who prepared it have proceeded beyond designing for the yellow note pad, or possibly the hard-back textbook.

In fairness to the Web --- or at least to those who have developed pedagogical resources for it --- text and images were almost the limit of its capability up until 1996. Certainly cumbersome interactively was possible through cgi scripts earlier, but although welcomed, the pedagogical usefulness of it was small by comparison to that which the teacher could offer locally through proprietary software such as HyperCard, Toolbook, or Director.

But, 1996 has changed all that. With the advent of Netscape 2.0 (and subsequent versions) with its plugin technology, one could build interactive pedagogical animations to aid students in the visualization of concepts or processes, and these then become available not only in the classroom, but the dormitory room, and indeed, anywhere on the internet.

The fact that this is now possible certainly brings into sharper focus the question of why a teacher might wish to do build such resources for the Web. Let us break the question into two parts: the usefulness of the pedagogical resources; the consequences of publishing them on the Web.

Visualizations

An important aspect of teaching is that of smoothly slipping one's own mental constructs into the minds of students. The computer facilitates this in ways unimaginable in the past. Previously, one might have had a mental model of some process, but to communicate it to students, it would have had to be turned it into words, metaphors, equations, and a few line drawings. The students would then use these as building blocks in their attempts to reconstruct the original mental model within their own minds. These attempts were rarely better than partially successful.

Now one can create a computer visualization --- maybe in the form of an interactive animation --- which enables the mental model to be more smoothly slipped into the students' minds. A larger fraction of the class can now internalize the concepts successfully. This not only changes how one handles traditional topics, but even what topics one can present: concepts previously deemed too complex for a low-level course can now be understood when mediated by an effective visualization.

A succession of student surveys and final examinations provides systematic, if anecdotal, evidence that this approach does indeed increase the accessibility of concepts to students. It seems clear that, at least to this biased observer, that an effort devoted to reinventing the way a concept is communicated now that the constraints of the blackboard have receded, brings benefits to one's students.

Access

Prior to the Web, a student in a class where computer visualizations were frequently offered was presented with a problem: how does one capture the material for later reflection and study. Note taking has its deficiencies; indeed, it was the very inadequacies of this sort of textual approach which had prompted the development of the new resources in the first place. Various approaches have been tried (collections of screen dumps available from the local copy house; copies of the software available in local laboratories) with modest success. But, they pale by comparison to platform-independent resources available over the Web to any classroom, dormitory room or home.

Now a student can explore the same materials used in class by the instructor and do so from virtually anywhere, at any time, and as often as needed. Again, to this biased observer, the advantages are palpable.

Making it work

An acknowledgment that the Web is now capable of delivering such material into the classroom and dormitory room, does not provide much insight into how to go about developing it. Indeed, as anyone who has seen a Web browser used as if it were satisfactory presentation software (instead of what it is, a way to browse the internet), will acknowledge, there is work to be done before it can be effectively employed directly in the classroom.

The mechanism by which one turns a Web browser into a effective means of presenting a whole course's worth of material in a classroom is fairly involved. Suffice to say here that the approach adopted involved building a special classroom interface. When the course is entered, the standard browser controls vanish and a new set (created using frames and JavaScript) appear. These provide easy access from any screen to features such as the hierarchical structure of the course, the default forward and reverse path, history, help screens, a glossary, and standard supporting resources of use in both the classroom and dormitory.

Equally important is the establishment of a convention for the navigation and exploration of resources such that it will be obvious after a couple of minutes of orientation how to find and understand material from anywhere in the course. This has been done by adopting a convention which specifies the order in which buttons of various shapes and locations should be explored.

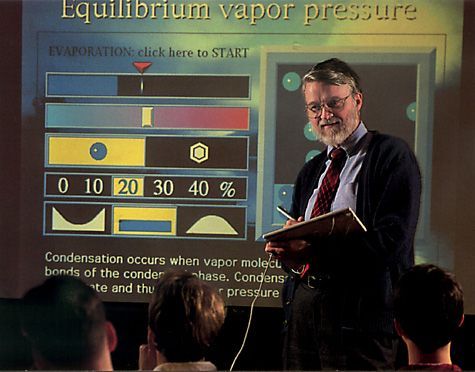

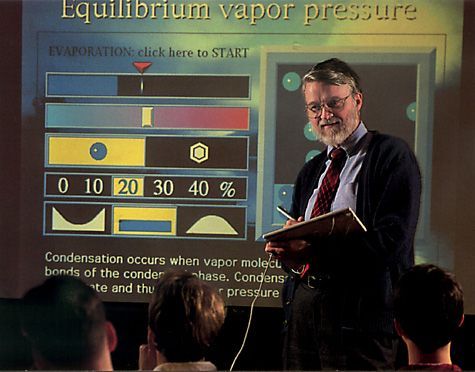

In practice, then, the instructor stands by a large projection screen at the front of the class and remotely controls the computer from which material is projected (see the picture above). The instructor proceeds as in any normal class --- by lecturing, promoting discussion, posing questions, even cajoling, and generally interacting with the students --- but he or she also has a powerful suite of resources to help present and promote the understanding of the material. And, outside the classroom, the students can continue to interact with the same resources.

Curious implications

Let us imagine that a whole course has now been developed and deposited on a Web server. It contains text, graphics, photographs, video clips, self-running animations, interactive animations and pedagogical models the parameters for which can be chosen by the user --- in short, everything the instructor would want to supplement and elaborate on every topic in the course. The instructor uses the material to facilitate explanations in class; the students use the material outside of class to not only review, but make further explorations of the concepts.

Such is the case for an introductory course in meteorology I teach. But if all of resources are available to the instructor and his students, they are also available to any other instructor and student on the internet. Indeed, this was one of the design criteria: from the same server, the course is offered on both the main campus of Penn State University and one of its many branch campuses. In this way we can offer courses on our branch campuses for which the numbers would have not previously justified it.

But, if the material can be used on one of our branch campuses, it can be used anywhere in the world (assuming that we do not limit its accessibility by domain, which we have no plans to do).

There are presently six hundred institutions of higher education in the U.S.A. which teach a vaguely comparable introductory meteorology course. Eighty percent of those courses are taught by non meteorologists. Would a handful of those instructors find it useful to have all the resources needed to deliver their course available through their university's backbone. It is at least conceivable that some would. Then, what about all those Earth Science courses in high schools, and this ignores all of the rest of the world.

Now imagine, as will happen, that every discipline creates such resources at all levels and makes them available to the world. How will courses be offered. Will a student sitting at home, but titularly enrolled in a college in one state find herself taking an English course which has its resources brought in from Harvard, a chemistry course from Princeton and a meteorology course from Penn State University? And if so, the question of the function of the local instructor will be brought into much sharp focus. Over the next decade as high quality interactive resources are delivered into classrooms and dormitories across the world, we can expect that our profession as teachers will evolve more than it did over the previous century.

But, if the role of teachers will evolve, one might expect the role of universities to evolve even further. At present, most universities operate in much the same way as did the computer firms of more than a decade ago: they attempt to offer the total solution. Just as a computer company used to try to trap a customer into buying everything from itself --- basic machine, peripherals, operating system, software, maintenance contract --- universities now provide students with virtually all of their classes, their books, board, room and then toss in a social life. The computer industry was forced to go to an open structure with boards, peripherals, and software being offered as plugins from a wide variety of suppliers. Will, the universities be able to make the transition to an open structure in which many of the undergraduate credits arrive from a dozen or so different off-campus sites? (Some of these sources may well be from businesses set up to provide such resources, rather than from other universities). With the potential for a student at one location ---home, say --- to take courses from many other locations and taught by professors at even other locations, what will be the function of the undergraduate institution, itself? When the physical plant ceases to be the gathering place for students or teachers, will a university's survival turn on its role as an agent of certification? Alas, even the power to award degrees is a power bestowed from elsewhere in the society, so it too might pass. Look for tumult in the ranks of undergraduate institutions over the next decade or so.

Coda

Following the ideas laid out in this essay, course resources entitled, Introductory Meteorology, are being built. You are welcome to explore them, but bear two things in mind: there are fairly stiff technical requirements for entrance (discussed on the set-up page); not all of the material is in place as yet.